Yes, there’s a question mark in this entry’s title. That’s not a mistake. But more on that later.

Filial piety is a key virtue of Confucianism. Confucianism is, in some ways, a counterpoint religion to Taoism, which I wrote about earlier. Both believe in the fundamental nature of a Tao, or Way (both in the sense of a path and a manner of doing). Both believe in structuring one’s life after the pattern of that Tao. They differ, though, on what the Tao is. For Taoists, the Tao is the Way of Nature – the way in which natural forces act and interact. For Confucians, the Tao is the Way of Civilization – the way in which civilized, cultured humans act and interact. It is very much “the way things are done around here.”

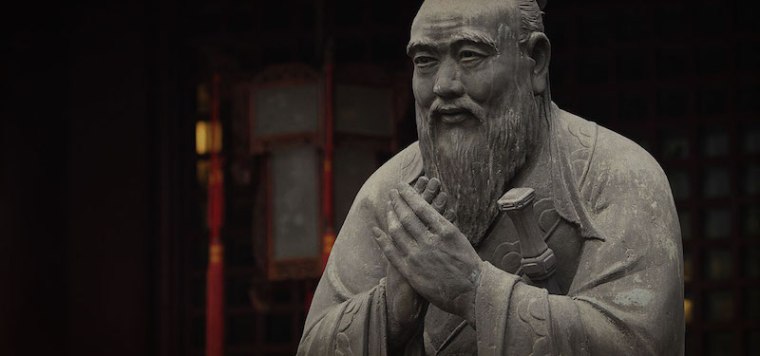

Confucianism is based in the teachings of Confucius (Kung Fu-tse), a Chinese sage who was born (most likely) in the 6th Century BCE. Confucius was a teacher. An upper-class man himself, he was charged with teaching the sons of his fellow noblemen the virtues and practices proper to their class. Confucius was decidedly conservative in outlook; he believed that the Tao was best exemplified in the ways of legendary rulers who lived centuries before his birth (much in the ways that European views of chivalry got traced to mythical figures like King Arthur). About his own teaching, he is reputed to have said, “I am a transmitter, not an innovator.” The Tao of Confucius, in other words, is very much about tradition. It is also about proper action. Confucius is known for a formulation of the Golden Rule (“Do not do to others what you would not want them to do to you”), but he also emphasized what is known as the rectification of names, or, essentially, “getting your place right.” This means knowing how to act properly in social situations, whether at home with family or at court with royalty. The Confucian Tao is in some ways a raising of etiquette to a way of life.

This means that Confucianism has already been mined elsewhere for workplace insights, as well as just good manners. I want to zero in on the virtue of filial piety because it is an unusual one in the Western world. Filial piety is the proper devotion shown by a child (for Confucius, particularly a son) toward a parent. It is a combination of respect and imitation. Here are a few sayings from the Analects of Confucius that help fill it out:

“Behave in such a way that your father and mother have no anxiety about you, except concerning your health.” (2.6)

“If for the whole three years of [socially prescribed] mourning a son manages to carry on the household exactly as in his father’s day, then he is a good son indeed.” (4.20)

“A young man’s duty is to behave well to his parents at home and to his elders abroad…” (1.6)

“Those who when young show no respect to their elders achieve nothing worth mentioning when they grow up.” (14.46)

In our culture, we often think of rebelling against our parents’ ways as a means to distinguish ourselves. Not so here. Parents deserve respect, and should repay respect with care and mentorship (this is also the template for good government – Confucianism literalizes the metaphor of a ruler as “father of the country”). Children distinguish themselves by embracing, living, and passing on what their elders have done. This is actually not so foreign a concept as we think. I would often begin lessons on Confucianism by asking my students etiquette questions: What should you wear to a funeral? What should you not wear to a wedding? How do you negotiate all those forks at a formal dinner? Who opens doors for whom on a date? And so on. Then I’d ask how they knew their answers. The replies were almost always (give or take a high-school course of some kind) “from my mom/dad/grandmother/grandfather.” My rebellious young people were a lot more used to following their elders’ patterns than they realized!

Filial piety represents a major theme in Confucianism – the importance of knowing and carrying out traditions because traditions encapsulate important knowledge. Confucius realized that our traditions make us who we are, for better and for worse. To be aware of tradition is to not feel the need to reinvent the wheel, and also to understand how we are indebted to those who came before us. Confucius would have agreed with T. S. Eliot when he wrote: “Some one said: ‘The dead writers are remote from us because we know so much more than they did.’ Precisely, and they are that which we know.” Our parents and their parents and their parents form a great deal of what we know, and what we do.

How might we adapt Confucian ideas about filial piety for teaching? Obviously, Confucius was himself a teacher, and what we have collected in the Analects are bits of his lessons. There is much to recommend good manners in the classroom, and, as I said, Confucius’s ideals are often held up as ways to get along with others. The focus on filial piety, though, allows us to zero in on the concept of tradition, and how that concept factors into what and how we teach. What is a tradition? What traditions are we, our subject matter, and our students parts of? How do we know? What does that mean for us? Who are our pedagogical “parents,” and how are we relating to them? Here are some things we might gain from teaching with an eye on filial piety:

Respect – It’s best to start where Confucius does, with respect for traditions. Innovation is a good thing in teaching, but any good teacher also knows you need to master the fundamentals first. Confucius believed that there were certain things a gentleman simply should know to be a civilized person. Something like this also lies behind the Liberal Arts in the Western world – historically, these were the areas of study that “liberated” people to pursue a good life. Filial piety in our academic setting means respecting what has come before, and emphasizing that there is more to what our students study than checking boxes for graduation. “Well-rounded” is not just a word for resumes. It is a goal of education as a whole. Our traditions last for a reason. Ideally, we are passing on those things that make us better, more civilized people. Part of this respect is also reminding students that they do not study in a vacuum. The reason for research is to become aware of what others have said and thought about the very same things they are studying now. There is a reason to learn the specialized terms and practices and formats of your chosen discipline – they mark you as being part of the tradition of that discipline. What might it mean to think of MLA format not as a way to pacify grumpy English professors, but as carrying on the ways of your literature-studying mothers and fathers? Jobs, too, have traditions – and learning early to recognize and embody traditions is good preparation for any field.

Relationship – Tradition isn’t a dead thing for Confucius. It’s based in interactions (reciprocity is another key Confucian value). With filial piety in mind, we can also work to help our students (and ourselves!) not just “study” traditions, but interact with them. Like my students who realized more of their ancestors’ ways lived on in them than they might have thought, we can look for surprising ways that the past remains relatable. I often told students in my literature courses that much of our concept of “genius” goes back to the Romantic Age – the person so full of passion and insight that it has to overflow into creativity. Your friend who stays up all night recording songs in her home studio is carrying on that tradition. This orientation encourages students to not think of subject matter as something only in a book or in a box in some kind of academic museum, but as something to interact with. The past is, as has been famously said, “a foreign country” insofar as it is different from our time – but inasmuch as it is our past, we are bound (as Eliot hinted) to have some familiarities with it. Are Greek funeral games in the Iliad so different from how we remember our sports stars, like Kobe Bryant or John Madden? Can you see your high-school dating life in A Midsummer Night’s Dream? It is easy to call things classic, important, or timeless without really delving into why. Confucian filial piety encourages us to specifically look for what is good about what we bring forward from our ancestors.

Constructive Criticism – but here’s where the question mark in the title comes in. As indebted as we are to our ancestors, we also all know that “because that’s how we’ve always done it” can be a terrible justification for action. Confucius saw carrying forward the ways of the ancients as a path to goodness. From our standpoint, we should use that standard also to critique what we bring forward. Just as we look for what is positive and enriching in our traditions, we should encourage students not to be afraid of also looking for what is negative or harmful in those traditions. Confucius was a conservative, but he was also an educator. Another of his sayings is, “He who learns but does not think is lost. He who thinks but does not learn is great danger.” There is, in other words, need for both taking in content and reflecting on it. And because traditions are living things, they can adapt. It is not a matter of completely rejecting or accepting tradition, but considering what in the tradition is a path toward greater civilization and goodness (and paths meander and shift). To think in terms of a relationship of filial piety is to think in terms of interacting with the “family” that preceded us, and families (I don’t have to tell you) are complicated. Plus, Confucius does not address how to judge a good son when the three mourning years are done. At some point, he becomes the new father figure whose ways will be emulated. How should he act then? What will encourage his children toward greater goodness, reciprocity, and liberation? How do we best honor our elders? By mere imitation? By building on their intentions? By correcting and refining their ideas? There are the beginnings of many hard but good conversations here.

Reflection questions:

- What traditions are important to what you teach? How mindful are you of them when you design and run classes?

- What traditions are you and your students parts of beyond the classroom? Family traditions? Political traditions? Religious traditions? Traditions related to sports, hobbies, or other activities? Are you aware of how you bring these traditions to your teaching and learning?

- Do you ever discuss with students why the content of your course is what it is? What do you hope students will take away from your course in terms of values or life skills? Does your material emphasize those things?

- What would it mean to you to think of education as a path to goodness and civilization? What practices would follow from such an understanding?

- Do you treat what you teach and study with respect? How so? Can students tell? How can you encourage them to do likewise?

- Do you create space for students to critique what they study? How can you help them do this in a constructive way?

- What does proper behavior in your classroom look like? What in your course practices and materials reinforces it?

To go a little deeper:

- The best place to start with Confucius is with the Analects, which collects his sayings along with the sayings of other sages. There are many, many print editions available, as well as versions online, such as this one: http://classics.mit.edu/Confucius/analects.html

- Eliot’s remark is from his essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent.” It is also widely available, including here: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69400/tradition-and-the-individual-talent Eliot himself is a good example of complicated traditional family – a seminal literary figure whose politics and attitudes we would not want to adopt wholesale today.

- Another interesting classic take on literary tradition is Harold Bloom’s The Anxiety of Influence (1973). In the way Bloom sees writers as embracing but wrestling with their predecessors, there’s an intriguing middle ground between filial piety and midrash (which I wrote about earlier).

- On the government side of things, two books I found interesting for thinking about political traditions and goodness are Jeffrey Stout’s Democracy and Tradition and Parker J. Palmer’s Healing the Heart of Democracy, both of which embody respectful but critical thinking about the history & practices of American politics.

- If you have students who are fans of the Disney+ series “The Mandalorian,” you have an easy Confucian entry point. The Mandalorians of the show have a very specific set of beliefs, actions, and interactions which define them, and they explain them by approvingly saying “This is the Way.” Confucius was up to something similar. This stuff really is all around us, if you know where to look…