Midrash is name for both a genre of Jewish religious texts and the practice which generates those texts; it is both a kind of literature and an activity. It is tricky to easily define. The word midrash is derived from a Hebrew root with at least as many shades of meaning as there are scholars of midrash. Among meanings given by people who write about midrash are “to search out” (Barry Holtz), “investigation” (Jacob Neusner), “to seek, to examine, to investigate” (Naomi Mara Hyman), and “research” (James Kugel).

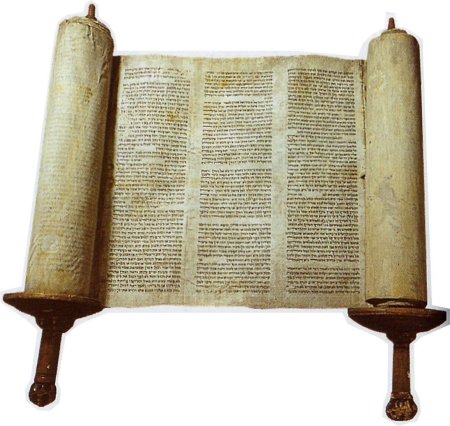

We can, however, find a point of agreement: midrash is practiced with and around scripture. It is therefore a process and a body of texts whose primary subject is other texts—particularly scriptural texts. For the rabbis who practice and create midrash, these other texts have value. They are important traditional texts, and when they were found to contain problems or be in need of explanation, rather than abandon them, the rabbis created new texts around them. A “faulty text,” as Barry Holtz explains, is for midrash “not a difficulty; it is an opportunity.”[i] The motive behind midrash is not a desire for completely new stories but for new relevance for old stories—not so much pure invention as “uncovering what is already there,” hidden behind difficulties or lapses.[ii] The interesting part about midrash, though, is that it aims to put these “hidden” discoveries alongside what is plainly already there. Midrash, according to Debra Orenstein, “infuses the values and concerns of later generations into the biblical text, even as it infuses biblical values and concerns into later generations.”[iii] In other words, midrash sets up and embodies an encounter between the original traditional text and contemporary interpretive texts. It is interaction. Midrashim often take the form of successions of quotes from various rabbis (from various time periods). The stories in them “speak” to each other; they are literally brought into dialogue.

In addition to being a form of textual encounter, midrash also serves as a form of textual repair. Midrashim often correct gaps, problems, or inconsistencies in the scriptural text. The Bible is, as many scholars note, famously and variously laconic – dwelling lavishly on certain details while completely omitting others. “Midrash,” writes Holtz, “comes to fill in the gaps, to tell us the details the Bible teasingly leaves out.”[iv] These omissions can include lapses in time, details of place, or thoughts and motivations of characters. A famous example of this is the exact thoughts of Isaac as Abraham led him to sacrifice. A different sort of gap deals with actual physical problems in the text—misspellings or omitted words. The underlying idea is, once again, that the Biblical texts are worth keeping despite these gaps and inconsistencies, and the method for correction is the creation of new texts. Various “problems” that occur in Biblical texts are “corrected” by putting new stories together with the traditional stories. This method works because of the concept discussed above: that texts can encounter and affect one another. New texts do not replace the old, problem-ridden texts, but exist alongside them. The result may therefore be less an end to an inconsistency or contradiction than a new approach to it. The idea is that it is better to continue with a patched-up tradition than to completely abandon it on account of its flaws.

Here is an example of what midrash looks like:

Rabbi Levi said in the name of Rabbi Chama bar Chanina: Three creations created The Holy One, blessed be He, on each day: on the first, heaven, earth, and light; on the second, the firmament, Gehenna, and the angels; on the third, trees, herbs, and the Garden of Eden; on the fourth, the sun, the moon, and the constellations; on the fifth, birds, fish, and the Leviathan; on the sixth, Adam, Eve, and moving creatures. Rabbi Pinchas said: On the sixth He created six things: Adam, Eve, moving creatures, cattle, wild beasts, and demons. Rabbi Benayah said: “That God created and did/made” is not written here, but “that God created to do/make”: All that the Holy One, blessed be He, would have created on the seventh, He did earlier and created it on the sixth. (Bereishit Rabbah 11)

The “gap” or the problem here is the details of God’s creative activity in the familiar “days of creation” story from Genesis 1 & 2. Notice how the rabbis’ musings are presented here, right up against each other. No one voice is presented alone, or as inescapably “correct.” Notice that their methods differ. Some uncover special meanings to numbers. Some look carefully at the construction of phrases. There is variety here, and that is desirable. But there is also unity: all the rabbis are close readers; they are paying focused attention to the text at hand. They are not making things up “off the top of their heads.” They thoughtfully consider the details that are available, and explore possibilities that open out from those. Those possibilities, in turn, give rise to others as the chain of consideration carries on.

What might we take from midrash for teaching? It is a fascinating subject in its own right, but it also has a lot to recommend it as an approach to texts. Of course, we should not all become rabbis, and there are plenty of dangers in conceiving of any classroom text as “scripture!” But to try on the “midrashic” mindset is to look at our course content with attention and with the attitude that difficulties really are opportunities. What might be “hidden” in our materials? What would it mean to go looking for it? How can we train our reading/listening/experiencing attention? Are we comfortable holding multiple perspectives next to each other? Might we try to creatively “repair” problematic stories or ideas? Here are some things we might learn from adopting a midrash-like sensibility in teaching:

Charity – To look at texts (or maybe your own lesson plans!) with a “midrashic” attitude is to adopt what is called a “hermeneutic of charity.” That’s a fancy phrase for “interpreting generously” or “giving the benefit of the doubt.” Remember that a major underlying assumption of midrash is that the texts it exists around have value. Thus, we would want to teach students to approach what they read in that mindset and ask first “what is valuable here?” Now, that may not mean it is easily or uncomplicatedly valuable. Remember that midrash thrives on problem areas and often involves repair. But understanding material in this way is a hedge against dismissing it beforehand or at the first sign of unease or difficulty. It is often a useful method to ask students to particularly highlight (through surveys, forms, emails, etc.) the parts of a reading that cause them difficulty, and begin investigation there. Jewish scholars are fond of the metaphor of “wrestling with a text,” based in the story of Jacob wrestling an angel until he receives a blessing. To teach with midrash in mind is to teach with the conviction that understanding may be hard work, and may involve wrestling a little (or a lot), but that the ultimate result is worth it. Something good and useful will emerge – even if it’s the determination never to wrestle with a particular text or kind of text again. It starts, though, with a sort of kindness toward the material, with the understanding that kindness can be a challenge, and a worthwhile one.

Creativity – Midrash is a genre and a practice. So practice it. Another underlying value of midrash is creative problem solving (that’s the whole point, in some ways). Difficulty is not a reason for despair, but for trying something new. Remember, though, that the rabbis never just made things up. Instead, the challenge here is to a kind of considered creativity, where we sit for a while with what troubles us, and try to find solutions or new approaches in context. After identifying the problem areas, go back to the comfortable ones. See if anything there helps. If not, why not? That may be a further clue to something that’s missing – something we could creatively provide. Novelist Madeleine L’Engle tells the story of a workshop she led once, where participants had to deal with scripture stories. One woman chose the story mentioned above – Abraham and Isaac, where the command to sacrifice his son is commonly seen as a test for Abraham, and Abraham passes. This woman, however, turned the story on its head – maybe Abraham failed! L’Engle says that “all kinds of lights flashed on” for her when she heard this. This was midrash. This new perspective was hidden in plain sight, in the original idea of the test. The logic of the story remains, but the traditional use of that logic is subverted with interesting results. We might adapt this to create assignments that encourage considered creativity. Or we might just start with a question, and ask for stories that answer that question. An important lesson for students here is that they have something to contribute. Midrash is about adding, not subtracting – expanding, filling in, and deepening. And that something comes from us, the readers and us, the storytellers.

Openness – No one “wins” midrash. It is not a quiz show. There is no rabbinic version of Mayim Bialik or Ken Jennings proclaiming that someone got the correct answer – or the correct question! Instead, midrash is dialogue. A multiplicity of views is seen as a good thing. If there is a winner at all, it is the community who receives all these possible answers to think about and creatively consider. We might look for ways to make our classes such a community, and to create assignments or activities that foster dialogue. There is a learning curve on this; we are not used to letting things stand in tension with no clear winner (ever been part of an online comment thread??). Midrash invites us to let that go, however, and to be open to the idea that questions, especially interpretive questions, have varying answers. Obviously, facts are facts. I would like to be able to repair the fact that my vision gets worse with age, or the fact of gravity (sometimes) – but that’s not what this is about. Remember that midrash focuses on scripture – on stories or rules with deep meanings or that address big questions. There is a reminder here to be open to others’ answers to these big questions or to their attempts to unravel those meanings. It may be that their answers make us consider something we had not before (as in L’Engle’s story). It is intriguing to think of scholarship not on the quiz show model of finding a predetermined answer, but as a quest for a series of answers. I remember hearing as a graduate student that I should think of my papers not just as assignments, but as my entries into wider, ongoing conversations about the topics. This is something I in turn tried to share with my students. It is a reminder that learning is active and alive and is a matter of back and forth. Each response calls forth another response. That’s how we advance.

Reflection questions:

- How do you approach what you read and teach? What gives it value, for you? Are you willing to give it the benefit of the doubt? Do you expect your students to do the same? How do you communicate that, if you do?

- What is your approach to problems in texts or other content? What would it look like to focus on them rather than trying to breeze past them or write them off?

- What does “wrestling with a text” mean to you? Do you ever do this? How could you get students to do it with you? To do it on their own?

- What can you do in a class to foster and encourage focused attention? Is attention one of your learning outcomes? What would it mean if it was?

- What does considered creativity mean to you? Where could you use creative assignments to start discussion or reframe stories or issues?

- Is it strange to you to think of text study as a form of healing or repair? What would it mean to adopt those things as objectives in learning? In teaching? In writing?

- How do you define a tradition? What keeps traditions going? What role does attention play? What role does creativity play? What role does education play?

To go a little deeper:

- Holtz’s full essay is a good introduction to midrash. It can be found in Barry Holtz, ed., Back to the Sources: Reading the Classic Jewish Texts (Touchstone, 1992) [also cited below as an endnote]

- Any good anthology of religious texts will have some midrash examples, but you can also find some online. A good guide to sources can be found here: http://huc.edu/research/libraries/guides/rabbinic-literature/midrash

- Another good website to browse if midrash itself interests you is: https://www.myjewishlearning.com/category/study/jewish-texts/midrash/

- L’Engle’s story can be found in her book The Rock that Is Higher (Shaw, 2002). Her novel Certain Women is itself an interesting midrashic take on the story of King David and his family.

[i] Barry Holtz, “Midrash” in Barry Holtz, ed., Back to the Sources: Reading the Classic Jewish Texts (Touchstone, 1992), p.180.

[ii] Holtz, p.185 (his italics).

[iii] Debra Orenstein, “Stories Intersect: Jewish Women Read the Bible” in Debra Orenstein, Jane Rachel Litman eds., Lifecycles: Jewish Women on Biblical Themes in Contemporary Life, Vol. 2. (Jewish Lights, 1997), p.xix

[iv]Holtz, p.180.